Teaming with Nature

My preoccupation with how humans name and order the natural world started at a very young age. I was drawing birds before I could write, mostly copying the works of John James Audubon, and when I would complete a picture I would ask my mom to write the name of the bird below the image. Somehow the drawing did not feel complete without the name of the creature.

At about nine years old I became obsessed with the trout that lived in the coldwater streams near my home in Connecticut. I began painting trout and wondered how many types there were. I searched local libraries for a book on North American trout to use as a reference. When I realized that a catalog of trout diversity did not exist I set out to make my own.

In my attempt to compile a list of the known trout in North America I soon learned that no two fish biologists could agree on how many types or species existed—how best to fragment and name the existing diversity appeared to be an open question. Some ichthyologists would call a certain western trout one species, the cutthroat trout, while others would divide the cutthroat unit into fourteen species. I was forced to wonder, even then, to what extent are such divisions in nature arbitrary? Does classification reflect reality? Are we in the process of discovering some existing natural order? Or, more often than not, are we imposing an order that does not exist for the purposes of comfort, convenience and communication?

My father was a staunch Darwinian who read the great popular evolutionary biology writers of the day —Stephen Jay Gould and E. O. Wilson among others. I became interested in big biological questions just from listening to him talk about what he’d read. At a certain point I felt equipped to ask my own questions, among them—how could you take the world as Darwin presented it, fluid continuous and constantly changing, and chop it into units in order to communicate it? The answer is that you cannot perfectly, but we must attempt to name and order things so we have a starting point for discussion .

Much of my work is now centered around questions that have been forming in my head since I was a child. What is the difference between the named world, the world we must label in order to communicate, and the unnamed world—the nature that cannot be bounded by terms and definitions?

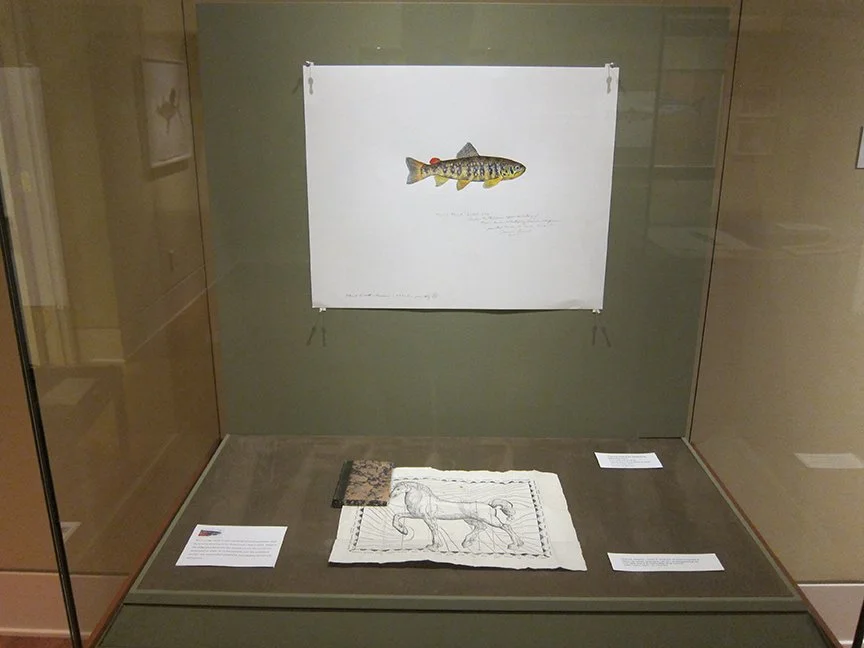

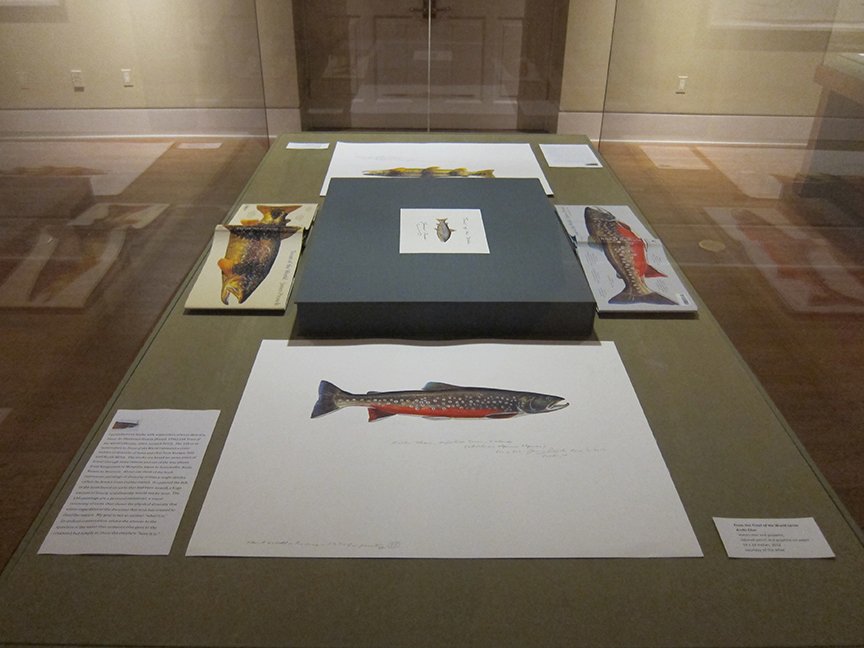

I published two books with watercolors of trout diversity, Trout: An Illustrated History (Knopf, 1996) and Trout of the World (Abrams, 2003, revised 2013). The 130 or so watercolors in Trout of the World represent a cross-section of diversity of trout and char from Europe, Asia and North Africa. The works are based on seven years of travel through some remote and out of the way places, from Kyrgyzstan to Mongolia, Japan to Kamchatka, Arctic Russia to Morocco. About one third of the book represents paintings of diversity within a single species called the brown trout (Salmo trutta). If I painted the fish in the book based on units that had been named, a huge amount of beauty and diversity would not be seen. The 130 paintings are a personal statement, a visual taxonomy of sorts . I wanted to show the physical diversity that exists regardless of the divisions that man had created to describe nature. My goal is not to answer “what it is,” (a cyclical conversation, where the answer to the question is the name that someone else gave to the creature) but simply to show the creature— “here it is.”

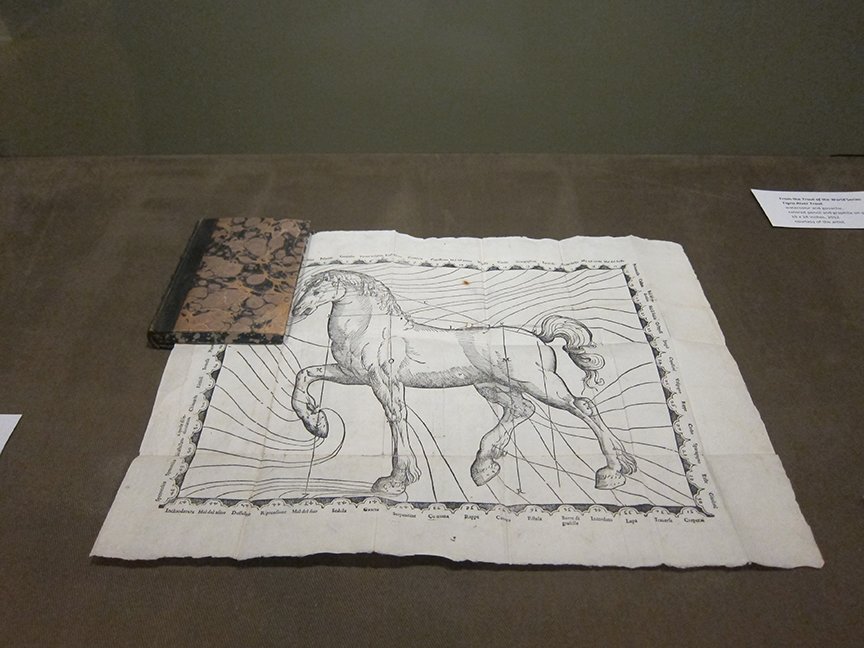

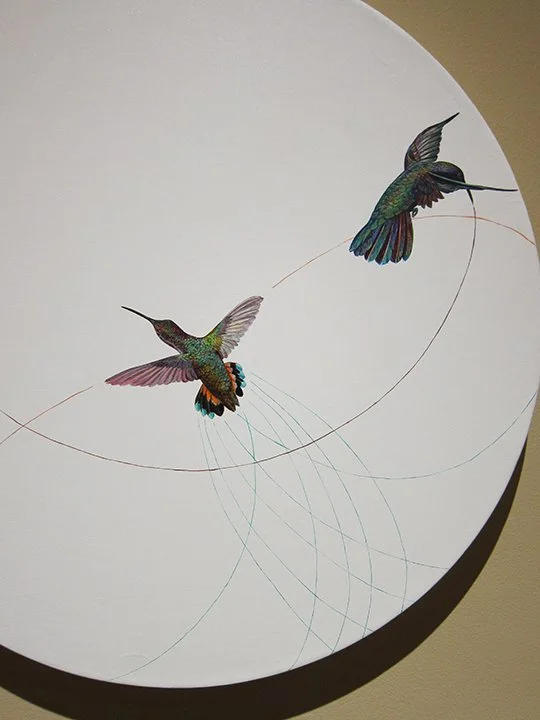

Subsequent works, made after the completion of Trout of the World in 2003 address themes and questions I encountered during the creation of these two volumes . Ultimately the inquiry is one of an artist and not a scientist and it is personal. The hybrid creatures were my first direct commentary on naming (see roosterfishe). They were creatures that had become their names in protest of being named, in spite of humans trying to control them through language (turtledove, parrotfishe, sailfishe, kingfisher). Nature will always be messy, will hybridize, will break out of the boxes we try to fit it into. Then I began making paintings of creatures with curvilinear lines emanating from points on their bodies. The point was not to do what had been common in traditional natural history painting—to paint the creature and write the common and scientific name beneath. I wanted people to look at the creature without having to say what it is—to satisfy their urge to know its name and then move on. The curvilinear lines, as I saw it, represented a non-verbal way of communicating a creature’s place in the ecosystem —a personal taxonomy, a visual taxonomy. I did not want to rely on the names and taxonomies others had given but encourage people to look for themselves, to have a personal experience and interaction with nature, untainted by the human stamp.

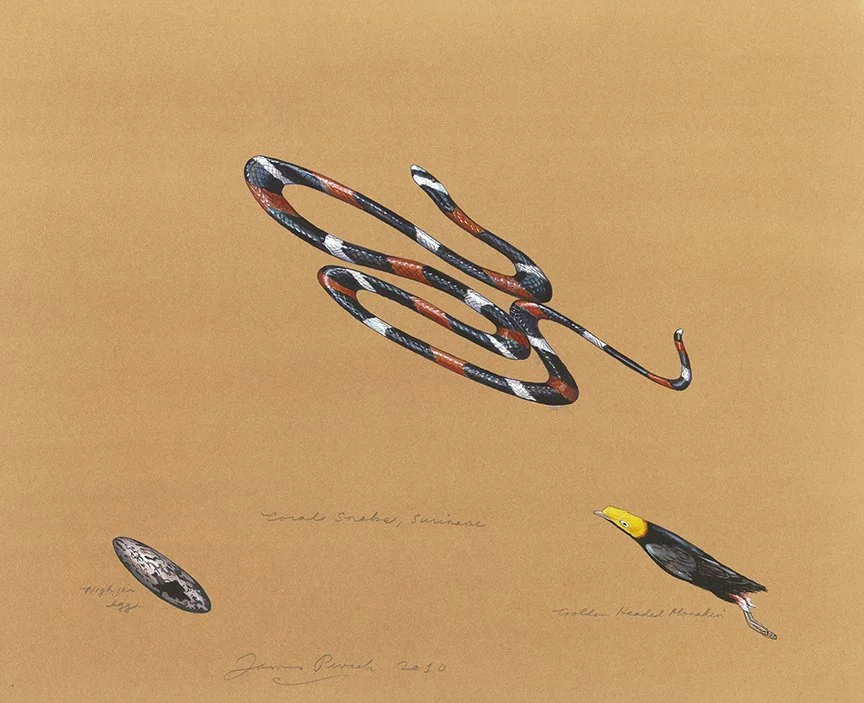

Other works in the exhibition like cobia, comment on the hierarchies in nature we create in our minds. In the painting I have made the decision to put the fish at the top of a trilogy of objects, a pyramid. Below are other elements, creatures or plants that live in the ecosystem of the fish. I could have chosen, as the artist, to put the eel-grass at the top of the pyramid, but instead the fish is there. It makes a statement about the sometimes-arbitrary nature of taxonomies and the decisions we make about how to order nature based on personal biases. The mechanical woodpecker (a red-bellied woodpecker with a drill bit for a beak) is a commentary on modern conservation practices. The creatures that we find most useful, or most beautiful, or that attract the most eco-tourists, get the most attention and are protected. So these “tool creatures” evolved to be useful, to mimic human industry, in order to survive. In addition to these works are a series of paintings I made on a collecting expedition to Suriname in South America with the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale. As part of my personal inquiry into how we name and order nature, it seemed essential to go on a trip where new species are searched for and named (in order to examine the physical process of naming).

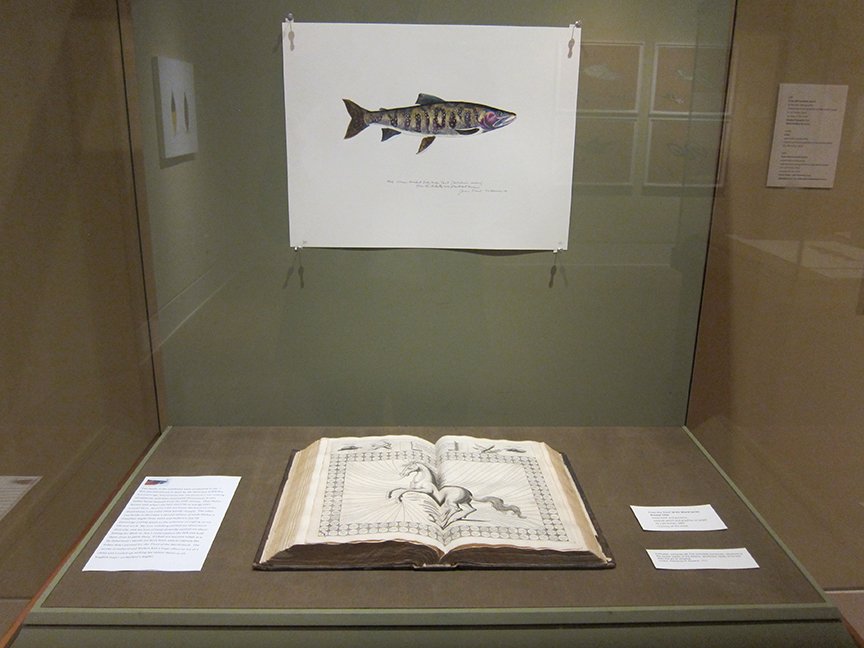

In the current National Sporting Library & Museum exhibition we have also installed, in cases, four objects from the permanent collection along with my paintings and three-dimensional works. Like the cobia painting these installations question how the juxtaposition of objects shape our perception of things in nature. A few of the installations are actual trilogies, with the painting at the top and the two three dimensional objects beneath. In two of the cases are flowers that I made out of clay. In a way, these three-dimensional works (that were made to look like real flowers) do what names do. A name freezes a creature, one that is in the process of evolving and changing, in a moment in time. A name gives us the illusion that time has stopped for us, and for this reason it gives us comfort, the illusion of immortality. In reality, over thousands or millions of years, the named creature will evolve beyond its name, and the name will represent only a segment of time in a continuum of intermediate stages of life. The flower made of clay takes a flower whose blossom is ephemeral, that lasts only a few days, and makes it bloom eternally. Like a name it also freezes time. This artificial flower is eternal, it requires no water, no atmosphere, no ecosystem, or life beyond itself to sustain it.

Two books in the exhibition were revelations to me. I first was introduced to them by the librarians at NSLM a few years ago, who noticed that the pictures I was making of creatures with lines resembled illustrations in two Italian horse manuals from the 16th century. They depict horses with what I can best describe as energy lines around them. Because I did not know the function of the illustrations I can enjoy them purely visually. The other two books in the cases, a second edition of Izaak Walton’s Compleat Angler from 1655 and Halford’s Dry Fly Etemology (1898) speak to the influence of angling on my life and work. My love of fishing excited me about trout diversity, and my love of trout diversity excited me about fishing for them so that I could capture the fish and hold them close to paint them. If I had not become adept as a fly-fisherman I would not have been able to capture (and examine up close) the fishes that I painted for the Trout of the World book. The works of Halford and Walton had a huge effect on me as a child and I ended up writing my senior thesis as an English major on Walton’s Angler.